Above: Echinacea purpurea, an important immune system stimulant in our medicinal plant collection

Medicinal Plants

The Imperative for Cultivating Herbal Antivirals and Herbal Antibiotics

Through indiscriminate use of pharmaceuticals we humans are breeding drug-resistant bacteria and viruses. By contrast, plants have learned to fight pathogens over the millennia by synthesizing far more complex compounds. We humans can use these to fight disease, strengthen our immune system, and improve our health.

We began our foray into plant medicine in the late 1990s when we realized the drawbacks of pharmaceuticals. First, pharmaceuticals are often based on a single active ingredient, often borrowed from plants, thereby ignoring the complex defenses plants mount against their own infective agents. Second, the synthesized compounds in pharmaceuticals often have multiple side effects, some severe. Third, pharmaceuticals often contain other substances. In hypodermic injections, these are called “adjuvants” which have contained toxic compounds including carcinogens, heavy metals, and aluminum. Fourth, in the case of flu shots, since there are so many strains for flu, a given season’s shot may not cover the flu strain you get. Fifth, pharmaceuticals treat symptoms and do nothing to help you strengthen your own immune system, which is our first line of defense against disease.

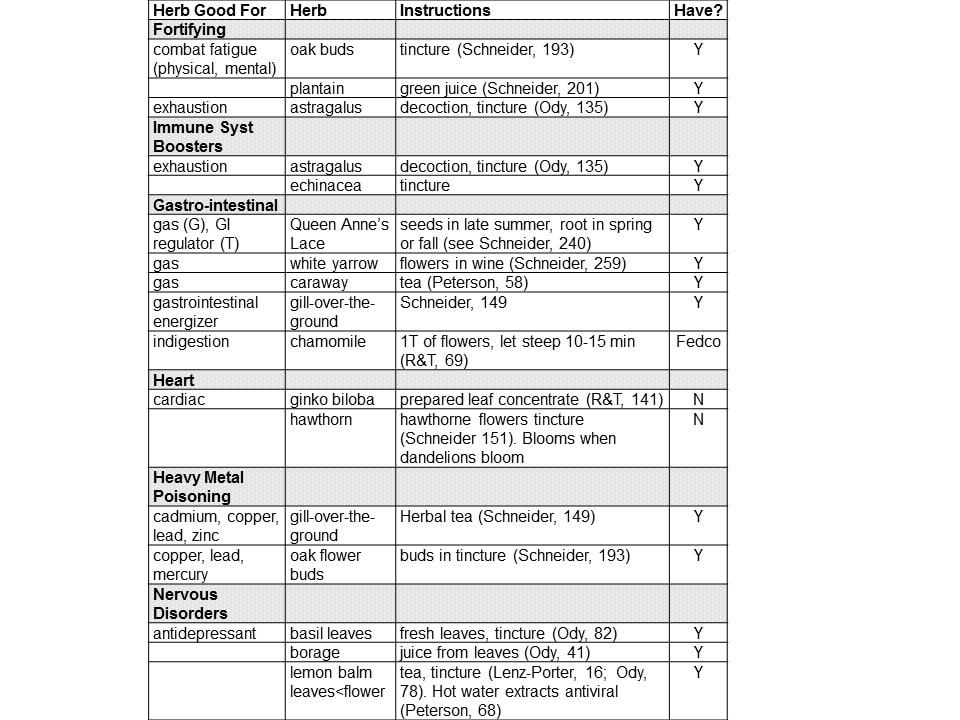

Our first step was to ask ourselves a simple two-part question: “What ailments do we suffer from or want to avoid, and what plants can we use to help us?” Using herbal reference books, we organized the answers to this question in a table which ultimately grew to four pages (we include page 2 of our table below). Our favorite overall reference at that time was James Duke's book The Green Pharmacy.

We gradually purchased seeds and began to grow several of these plants. We soon realized that some of these medicinal plants were already in our yard. Some were part of the landscape – bee balm (for sore throats), oak flower buds (to eliminate heavy metals from your body), hawthorne (for heart problems and anxiety). Others were growing as weeds! – plantain (for coughs and chronic respiratory conditions), gill-over-the-ground (liquefies mucus), and nettle (insect bites, wounds).

Through indiscriminate use of pharmaceuticals we humans are breeding drug-resistant bacteria and viruses. By contrast, plants have learned to fight pathogens over the millennia by synthesizing far more complex compounds. We humans can use these to fight disease, strengthen our immune system, and improve our health.

We began our foray into plant medicine in the late 1990s when we realized the drawbacks of pharmaceuticals. First, pharmaceuticals are often based on a single active ingredient, often borrowed from plants, thereby ignoring the complex defenses plants mount against their own infective agents. Second, the synthesized compounds in pharmaceuticals often have multiple side effects, some severe. Third, pharmaceuticals often contain other substances. In hypodermic injections, these are called “adjuvants” which have contained toxic compounds including carcinogens, heavy metals, and aluminum. Fourth, in the case of flu shots, since there are so many strains for flu, a given season’s shot may not cover the flu strain you get. Fifth, pharmaceuticals treat symptoms and do nothing to help you strengthen your own immune system, which is our first line of defense against disease.

Our first step was to ask ourselves a simple two-part question: “What ailments do we suffer from or want to avoid, and what plants can we use to help us?” Using herbal reference books, we organized the answers to this question in a table which ultimately grew to four pages (we include page 2 of our table below). Our favorite overall reference at that time was James Duke's book The Green Pharmacy.

We gradually purchased seeds and began to grow several of these plants. We soon realized that some of these medicinal plants were already in our yard. Some were part of the landscape – bee balm (for sore throats), oak flower buds (to eliminate heavy metals from your body), hawthorne (for heart problems and anxiety). Others were growing as weeds! – plantain (for coughs and chronic respiratory conditions), gill-over-the-ground (liquefies mucus), and nettle (insect bites, wounds).

Our next step was to figure out what to do with the herbs. Here we learned the differences among teas, decoctions, infusions and tinctures; the properties of herbs that made one or another mode of preparation more desirable; which parts of the plant were best for a particular ailment; when to harvest; how to prepare; protocols for use; and how to store.

In the background we noticed a growing buzz of concerns. Early on we began reading and hearing about resistance of organisms to synthetic compounds. First it was resistance of insects to pesticides. Then it was resistance of weeds to herbicides. Farmers had to apply even more potent and toxic chemicals. Their use began breeding super weeds. Since we were organic growers, these two trends didn’t affect us directly.

What got our attention was resistance of disease-causing microbes in humans – us -- to antibiotic and antiviral medications. The alarming message underlying this development was that modern medicine was running out of ways to combat infections, from which many of us could get seriously sick or die! Sir Alexander Fleming, discoverer and developer of penicillin, saw this coming, and warned his fellow scientists and members of the medical community way back in the early 1940s about overuse of antibiotics. No one listened. In short, the two of us realized that drug resistance was a much bigger challenge than our individual ailments. Moreover, the threat was imminent and growing. What to do?

Luckily small cadres of ethnobotanists, agriculturalists, scientists and herbalists were making use of our evolutionary history. We humans evolved from plants. Later on we evolved with plants. There is great wisdom in the plant community which we can learn about and use to our advantage. Traditional cultures have used plants to treat illness for thousands of years. Today two great cultures still practice plant medicine: Ayurvedic practitioners in India and Traditional Chinese Medicine (in China but increasingly worldwide).

The one person who turned our heads around on this point of microbial resistance was Stephen Harrod Buhner, author of two important books on plant medicine: Herbal Antibiotics (2nd edition 2012), and Herbal Antivirals (2013). Since 2014 we have taken his findings to heart and have begun learning about, growing, preparing and using herbal antivirals and herbal antibiotics. What we present in the next section draws from Buhner. Buhner may not be the last word on treating superbugs. On the horizon is a modality called phage therapy.

Buhner is one of a long line of important ethnobotanists. We've already mentioned James Duke, whose Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases serve as his lasting legacy. Perhaps earliest among these ethnobotanists was Richard Evans Schultes, famous for his botanical explorations of the Amazon. His protege, Wade Davis, wrote about Schultes' adventures in One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest. Now, on to Buhner!

In the background we noticed a growing buzz of concerns. Early on we began reading and hearing about resistance of organisms to synthetic compounds. First it was resistance of insects to pesticides. Then it was resistance of weeds to herbicides. Farmers had to apply even more potent and toxic chemicals. Their use began breeding super weeds. Since we were organic growers, these two trends didn’t affect us directly.

What got our attention was resistance of disease-causing microbes in humans – us -- to antibiotic and antiviral medications. The alarming message underlying this development was that modern medicine was running out of ways to combat infections, from which many of us could get seriously sick or die! Sir Alexander Fleming, discoverer and developer of penicillin, saw this coming, and warned his fellow scientists and members of the medical community way back in the early 1940s about overuse of antibiotics. No one listened. In short, the two of us realized that drug resistance was a much bigger challenge than our individual ailments. Moreover, the threat was imminent and growing. What to do?

Luckily small cadres of ethnobotanists, agriculturalists, scientists and herbalists were making use of our evolutionary history. We humans evolved from plants. Later on we evolved with plants. There is great wisdom in the plant community which we can learn about and use to our advantage. Traditional cultures have used plants to treat illness for thousands of years. Today two great cultures still practice plant medicine: Ayurvedic practitioners in India and Traditional Chinese Medicine (in China but increasingly worldwide).

The one person who turned our heads around on this point of microbial resistance was Stephen Harrod Buhner, author of two important books on plant medicine: Herbal Antibiotics (2nd edition 2012), and Herbal Antivirals (2013). Since 2014 we have taken his findings to heart and have begun learning about, growing, preparing and using herbal antivirals and herbal antibiotics. What we present in the next section draws from Buhner. Buhner may not be the last word on treating superbugs. On the horizon is a modality called phage therapy.

Buhner is one of a long line of important ethnobotanists. We've already mentioned James Duke, whose Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases serve as his lasting legacy. Perhaps earliest among these ethnobotanists was Richard Evans Schultes, famous for his botanical explorations of the Amazon. His protege, Wade Davis, wrote about Schultes' adventures in One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest. Now, on to Buhner!

Buhner's Top Antibiotic and Antiviral Herbs

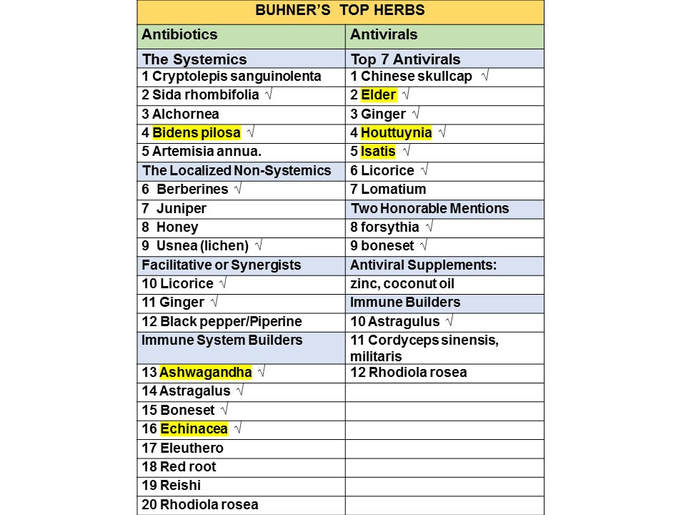

The table below lists Buhner’s top herbs. We have checked off those that we have recently grown, are now growing, or serendipitously already had in our yard (lichen – on trees! – and the common forsythia with its bright yellow blossoms and berries). Others are easy to get, e.g., honey and ginger. On honey, Buhner warns the reader to avoid clover and alfalfa, as these are crops and often sprayed with pesticides. Get raw wildflower from reputable if not local sources as there is much adulteration.

This table condenses a larger table we have prepared which you can download here. The larger table represents our attempt at summarizing key points from Buhner’s two books. We emphasize that there is a lot more information about the herbs and their uses than we can cover here. Important topics include contraindications, how to grow the herbs, and the copious research studies Buhner references. We have selected three antibacterials and three antivirals to explore further in the next section, and these we have highlighted in yellow in the table below. Should the growing or preparation of these herbs prove daunting, you can buy many of these, in raw form or tinctures. An excellent source for quality tinctures is Woodland Essence. For raw and bulk herbs, try 1st Chinese Herbs. We have purchased from both and recommend them.

We focus largely on tinctures as we can make a batch and store these for a considerable period of time. As the grain alcohol tinctures can be intense by themselves, you can add many of these to water or juice on ingestion. Echinacea angustifolia depends on direct contact with your throat to kill virus on contact, so minimize dilution. Depending on the plant, you can also make teas with the leaves and decoctions with the roots. However, Isatis, also known as indigo, produces an intense blue dye, so you would not want to chew the fresh leaves. When making decoctions, keep the pot covered to retain volatile compounds. For an excellent summery of how to make herbal preparations, see Chapter 8 in Buhner's "Herbal Antibiotics" titled A Handbook of Herbal Medicine Making or Appendix A in his "Herbal Antivirals" titled A Brief Look at Herbal Medicine Making.

At a workshop we gave, one of the attendees wondered whether the herbal remedies kill beneficial microbes. As I had not come across anything in either of his two books that speaks to this, I wrote to Stephen and received this reply: In general, no plants do not kill beneficial bacteria (but) the answer is complex with caveats. For Buhner's full answer, see endnote (1). Buhner is careful to point out contraindications for the herbs he profiles. You can get a sense of these by examining the last column in the summary table I have prepared, whose link is available two paragraphs earlier in the first sentence. I have used the code "SE,CI" for "Side Effects, ContraIndications."

This table condenses a larger table we have prepared which you can download here. The larger table represents our attempt at summarizing key points from Buhner’s two books. We emphasize that there is a lot more information about the herbs and their uses than we can cover here. Important topics include contraindications, how to grow the herbs, and the copious research studies Buhner references. We have selected three antibacterials and three antivirals to explore further in the next section, and these we have highlighted in yellow in the table below. Should the growing or preparation of these herbs prove daunting, you can buy many of these, in raw form or tinctures. An excellent source for quality tinctures is Woodland Essence. For raw and bulk herbs, try 1st Chinese Herbs. We have purchased from both and recommend them.

We focus largely on tinctures as we can make a batch and store these for a considerable period of time. As the grain alcohol tinctures can be intense by themselves, you can add many of these to water or juice on ingestion. Echinacea angustifolia depends on direct contact with your throat to kill virus on contact, so minimize dilution. Depending on the plant, you can also make teas with the leaves and decoctions with the roots. However, Isatis, also known as indigo, produces an intense blue dye, so you would not want to chew the fresh leaves. When making decoctions, keep the pot covered to retain volatile compounds. For an excellent summery of how to make herbal preparations, see Chapter 8 in Buhner's "Herbal Antibiotics" titled A Handbook of Herbal Medicine Making or Appendix A in his "Herbal Antivirals" titled A Brief Look at Herbal Medicine Making.

At a workshop we gave, one of the attendees wondered whether the herbal remedies kill beneficial microbes. As I had not come across anything in either of his two books that speaks to this, I wrote to Stephen and received this reply: In general, no plants do not kill beneficial bacteria (but) the answer is complex with caveats. For Buhner's full answer, see endnote (1). Buhner is careful to point out contraindications for the herbs he profiles. You can get a sense of these by examining the last column in the summary table I have prepared, whose link is available two paragraphs earlier in the first sentence. I have used the code "SE,CI" for "Side Effects, ContraIndications."

Focusing on Six Herbs

Antibiotics

(1) Bidens. Properties: Antimicrobial, antidiabetic, antidysenteric, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antimicrobial, antiseptic, blood tonic, immunomodulant, mucous membrane tonic, etc. Active against: bacillus cereus, candida, cytomegalovirus, E. coli, herpes 1 & 2, gonorrhoeae, salmonella, shigella, staph aureus, staph epidermidis, etc. Used to treat: (1) any systemic infection of mucous membranes; (2) systemic staph; (3) malaria, babesia, leishmania; (4) other resistant organisms.

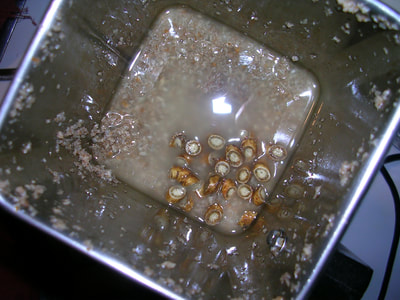

Standard prep procedure: 1:2 (means ratio of 1 oz fresh leaves : 2 fluid oz 190 proof grain alcohol). Harvest leaves before go to flower. Grind together in a blender. Put in jar with cap. Shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Then strain and run remainder through a wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in cool dark place. Residents of Pennsylvania will require a permit to obtain 190 proof grain alcohol for personal use. They can acquire this license from the PA Liquor Control Board by first registering for an account. Under the Licensing" tab click on PLCB+ and then on "Register here" and fill in the form.

Dose: Bidens is great for systemic infections. For acute conditions (malaria, systemic staph) take 1/4 -1 tsp and up to 1 Tbl in water, up to 6x/day for up to 28 days. Use with piperine as a synergist to help the main herb (bidens) cross intestinal barrier, but there are several warnings about using piperine in Buhner which you should consult. For example, you would NOT use piperine if you have an infection of the intestinal wall itself (e.g., cholera, E.coli) as piperine will help the bacteria cross into your body and become a systemic infection.

(1) Bidens. Properties: Antimicrobial, antidiabetic, antidysenteric, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antimicrobial, antiseptic, blood tonic, immunomodulant, mucous membrane tonic, etc. Active against: bacillus cereus, candida, cytomegalovirus, E. coli, herpes 1 & 2, gonorrhoeae, salmonella, shigella, staph aureus, staph epidermidis, etc. Used to treat: (1) any systemic infection of mucous membranes; (2) systemic staph; (3) malaria, babesia, leishmania; (4) other resistant organisms.

Standard prep procedure: 1:2 (means ratio of 1 oz fresh leaves : 2 fluid oz 190 proof grain alcohol). Harvest leaves before go to flower. Grind together in a blender. Put in jar with cap. Shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Then strain and run remainder through a wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in cool dark place. Residents of Pennsylvania will require a permit to obtain 190 proof grain alcohol for personal use. They can acquire this license from the PA Liquor Control Board by first registering for an account. Under the Licensing" tab click on PLCB+ and then on "Register here" and fill in the form.

Dose: Bidens is great for systemic infections. For acute conditions (malaria, systemic staph) take 1/4 -1 tsp and up to 1 Tbl in water, up to 6x/day for up to 28 days. Use with piperine as a synergist to help the main herb (bidens) cross intestinal barrier, but there are several warnings about using piperine in Buhner which you should consult. For example, you would NOT use piperine if you have an infection of the intestinal wall itself (e.g., cholera, E.coli) as piperine will help the bacteria cross into your body and become a systemic infection.

(2) Ashwagandha. Actions. Root most used: anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, immune tonic, nervine. Fruit: immune tonic. Leaves and stem: nervine, antitumor. Leaves also analgesic.

Preparation: Can use dry root, fresh leaf, dry seed, fresh fruit. I make separate tinctures of root and leaves. Root good for chronic conditions, leaves for acute conditions. For daily use I mix 50-50 in a dropper bottle.

- Root:

- Cut the root into small pieces with knife or pruners and dry on tray.

- Use a 1:5 ratio of dried root to 70% alcohol. Blend to a slurry. Put in jar with cap. Shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, run rest through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

- Challenge: you will not easily find 70% alcohol (140 proof). You can find 80 proof, 100 proof, and 190 proof. What to do? Use a little math. 70% alcohol means the balance is 30% water. For practical purposes, we consider 190 proof alcohol, at 95% alcohol, to be 100% alcohol. Thus, if you are going to make a tincture with 4 oz of ashwagandha root, you will require 4x5 or 20 oz of 70% alcohol. To get that, you will want 0.3 x 20 or 6 oz. of water and 14 oz of 100% alcohol. Measure out 14 oz of alcohol. Add 6 oz of water. Pour that into the blender with the chopped ashwagandha and blend to a slurry. Complete the steps in (2) above: blend to a slurry, put in jar, etc.

- Leaves:

- Use a 1:2 ratio of fresh leaves to 190 proof alcohol. Blend to a slurry. Put in jar with cap. Shake 2x/day for two weeks. Strain, run through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

Note: Ashwagandha is a member of the solanaceae family (tomato, potato, peppers, eggplant). It suffers from late blight (phytopthera infestans). We made PSU plant pathologist John Peplinski’s retirement year a special one when we brought in a sample of an infected ashwagandha plant. It was the first ashwagandha plant he had seen, and his test confirmed late blight! He published a unique note for a plant pathology journal.

(3) Echinacea.. Actions: Analgesic, antibacterial, antiviral, an immune stimulant and stimulates antibody production.

There are two medicinal varieties: E.Purpurea (purple coneflower) and E. Angustifolia. I have used E. Purpurea root tincture for years, in a protocol with garlic and cayenne 1/month for 6 days during the cold-flu season (November through March). Buhner asserts that E. Purpurea is not all that effective, compared to E. Angustifolia, and if you use E. Purpurea, follow the European practice: make a fresh juice by expressing the aerial parts through a juicer. You can stabilize it with alcohol. For acute infections of the throat, Buhner recommends a tincture of E. Angustifolia root, which I have also been making for the last few years. It kills microbes in the throat on contact, and should be the first line of defense when you get a tickle in your throat or feel a cold coming on. With practice, you will be able to catch the infection at its earliest stage. If you miss it, the microbes descend into your throat and lungs, where the tincture cannot touch it. When that happens, use other antivirals, e.g., elder, houttuynia, isatis.

Root Prep: Same as ashwaganda root. Harvest in the fall. Cut into pieces and dry. Same ratio of 1:5 as with ashwagandha above. As I was in a hurry, I used the fresh root. As it has water in it, I used a more concentrated form of alcohol, the 190 proof, and used the ratio 1:2. Grind in blender with alcohol, pour in jar, cap, shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, then run rest through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

Dose: Many applications, and each has a different dose. For onset of colds and flu, I squirt 3 or so dropperfuls in my mouth, head tilted up, and let the tincture mix with your saliva and drizzle down your throat. Repeat every hour until symptoms cease. It works miraculously, and you may find yourself much better the next day -- if you catch it early enough. Do not take longer than 3-4 days. Echinacea is more effective taken in conjunction with licorice and red root, but see Buhner's warnings on licorice. Other aids for a cold/flu include zinc lozenges (with elderberry), and ginger. With ginger, prepare in one of two ways:

(1) Juice fresh ginger to make 1/4 cup, add to hot water (12 oz), Add 1/4 lime squeezed, 1/8 t cayenne, and 1 T honey;

This makes ~ 2 cups. Drink 4-6 cups/day.

(2) grate ginger (piece the size of your thumb) and steep in 8-12 oz of hot water for 2-3 hrs. covered to preserve essential oils.

Drink 4-6 cups/day.

There are two medicinal varieties: E.Purpurea (purple coneflower) and E. Angustifolia. I have used E. Purpurea root tincture for years, in a protocol with garlic and cayenne 1/month for 6 days during the cold-flu season (November through March). Buhner asserts that E. Purpurea is not all that effective, compared to E. Angustifolia, and if you use E. Purpurea, follow the European practice: make a fresh juice by expressing the aerial parts through a juicer. You can stabilize it with alcohol. For acute infections of the throat, Buhner recommends a tincture of E. Angustifolia root, which I have also been making for the last few years. It kills microbes in the throat on contact, and should be the first line of defense when you get a tickle in your throat or feel a cold coming on. With practice, you will be able to catch the infection at its earliest stage. If you miss it, the microbes descend into your throat and lungs, where the tincture cannot touch it. When that happens, use other antivirals, e.g., elder, houttuynia, isatis.

Root Prep: Same as ashwaganda root. Harvest in the fall. Cut into pieces and dry. Same ratio of 1:5 as with ashwagandha above. As I was in a hurry, I used the fresh root. As it has water in it, I used a more concentrated form of alcohol, the 190 proof, and used the ratio 1:2. Grind in blender with alcohol, pour in jar, cap, shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, then run rest through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

Dose: Many applications, and each has a different dose. For onset of colds and flu, I squirt 3 or so dropperfuls in my mouth, head tilted up, and let the tincture mix with your saliva and drizzle down your throat. Repeat every hour until symptoms cease. It works miraculously, and you may find yourself much better the next day -- if you catch it early enough. Do not take longer than 3-4 days. Echinacea is more effective taken in conjunction with licorice and red root, but see Buhner's warnings on licorice. Other aids for a cold/flu include zinc lozenges (with elderberry), and ginger. With ginger, prepare in one of two ways:

(1) Juice fresh ginger to make 1/4 cup, add to hot water (12 oz), Add 1/4 lime squeezed, 1/8 t cayenne, and 1 T honey;

This makes ~ 2 cups. Drink 4-6 cups/day.

(2) grate ginger (piece the size of your thumb) and steep in 8-12 oz of hot water for 2-3 hrs. covered to preserve essential oils.

Drink 4-6 cups/day.

Antivirals

(4) Elder. Actions: As a narrow spectrum antiviral , e.g., herpes, flu, HIV, hepatitis B,C,D,E. West Nile, polio, rhinoviruses, SARS, shingles, chicken pox, dengue, Ebola, GI tract infections, measles, diphtheria, mumps, in particular enveloped viruses. As a nervine (relaxes nervous system), reduces arthritic & internal inflammations. Leaf tincture in small doses as analgesic.

You can use all parts of the elderberry bush – the blossoms, berries, stems, leaves, inner bark and root. The parts range in the order given from weakest (blossoms) to strongest (roots). It truly is a wonderful antiviral plant. The most common variety in the U.S. is Sambucus nigra, which has dark blue-black berries. Tania makes an elder flower cordial infusion with oranges, lemons, limes and sugar, which is refreshing on a hot day with some water and ice. She also makes a wonderfully tasty decoction of the berries which makes being sick bearable. Gene makes tinctures with the twigs and leaves. You can also make incredible cough syrups.

Prep. Warning! The elder plant contains cyanide compounds. In susceptible individuals, ingesting these fresh can cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, weakness. These compounds act as emetics (vomiting) or purgatives (diarrhea), which may be useful in helping individuals get rid of toxins in the body. Tinctures of the fresh parts can induce sweating, which is useful in lowering fevers during viral infections.

syrup, 6 cups water, 8 half-pint canning jars.

Steps:

1. Place berries/berries and stems with 6 cups water in pan, bring to boil, and simmer uncovered for 30 minutes. It is

important to start with cold water and bring to a boil. Different compounds come out at different temperatures.

Elderberries are not high in vitamin C, so minimizing cooking time is not valid. Starting with cold water maximizes

release of beneficial compounds. Boiling for 30 minutes inactivates cyanide compounds.

2. While berries are simmering sterilize 8 half-pint canning jars and lids.

3. After 30 minutes of simmering, strain out berries by pouring through a mesh strainer into another pot or bowl, and

gently press berries in the strainer to extract the most juice. Compost spent berries and stems.

4. Add lemon juice and maple syrup, bring to boil for a couple of minutes, turn off heat, fill canning jars, and can

according to canning instructions for canning fruit juice. For a steam canner, pint jars or smaller require 10 minutes

of processing plus 1 minute per 1,000 feet elevation above sea level. Makes 7-8 half-pints.

5. Store in cool dark place; will keep for several years. Label.

Note: In lieu of canning, one could cool and either refrigerate for immediate use, or freeze in flexible plastic containers

or as ice cubes to thaw for later use. If freezing, you can eliminate the lemon juice and maple syrup, and add sweetener on

thawing for use. .

Dose: As a decoction, take 1-2 T every 2-4 hrs in early stages of cold or flu. Refrigerate after opening. As a leaf tincture, 5-10 drops every 1-2 hrs.

(4) Elder. Actions: As a narrow spectrum antiviral , e.g., herpes, flu, HIV, hepatitis B,C,D,E. West Nile, polio, rhinoviruses, SARS, shingles, chicken pox, dengue, Ebola, GI tract infections, measles, diphtheria, mumps, in particular enveloped viruses. As a nervine (relaxes nervous system), reduces arthritic & internal inflammations. Leaf tincture in small doses as analgesic.

You can use all parts of the elderberry bush – the blossoms, berries, stems, leaves, inner bark and root. The parts range in the order given from weakest (blossoms) to strongest (roots). It truly is a wonderful antiviral plant. The most common variety in the U.S. is Sambucus nigra, which has dark blue-black berries. Tania makes an elder flower cordial infusion with oranges, lemons, limes and sugar, which is refreshing on a hot day with some water and ice. She also makes a wonderfully tasty decoction of the berries which makes being sick bearable. Gene makes tinctures with the twigs and leaves. You can also make incredible cough syrups.

Prep. Warning! The elder plant contains cyanide compounds. In susceptible individuals, ingesting these fresh can cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, weakness. These compounds act as emetics (vomiting) or purgatives (diarrhea), which may be useful in helping individuals get rid of toxins in the body. Tinctures of the fresh parts can induce sweating, which is useful in lowering fevers during viral infections.

- Cyanide compounds can be inactivated by heating. The procedure is as follows. For berries, stems, leaves, bark, or root, start with cold water and raise the heat, boiling for 30 minutes. This reduces the cyanide compounds to nearly nothing.

- You can use fresh parts or dried parts.

- For a fresh leaf tincture, use a 1:2 ratio with 190 proof alcohol. Grind in blender, pour in jar, cap, shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, then run rest through wheat grass juicer. Compost the marc. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

- To make a decoction, here is Tania's recipe:

syrup, 6 cups water, 8 half-pint canning jars.

Steps:

1. Place berries/berries and stems with 6 cups water in pan, bring to boil, and simmer uncovered for 30 minutes. It is

important to start with cold water and bring to a boil. Different compounds come out at different temperatures.

Elderberries are not high in vitamin C, so minimizing cooking time is not valid. Starting with cold water maximizes

release of beneficial compounds. Boiling for 30 minutes inactivates cyanide compounds.

2. While berries are simmering sterilize 8 half-pint canning jars and lids.

3. After 30 minutes of simmering, strain out berries by pouring through a mesh strainer into another pot or bowl, and

gently press berries in the strainer to extract the most juice. Compost spent berries and stems.

4. Add lemon juice and maple syrup, bring to boil for a couple of minutes, turn off heat, fill canning jars, and can

according to canning instructions for canning fruit juice. For a steam canner, pint jars or smaller require 10 minutes

of processing plus 1 minute per 1,000 feet elevation above sea level. Makes 7-8 half-pints.

5. Store in cool dark place; will keep for several years. Label.

Note: In lieu of canning, one could cool and either refrigerate for immediate use, or freeze in flexible plastic containers

or as ice cubes to thaw for later use. If freezing, you can eliminate the lemon juice and maple syrup, and add sweetener on

thawing for use. .

Dose: As a decoction, take 1-2 T every 2-4 hrs in early stages of cold or flu. Refrigerate after opening. As a leaf tincture, 5-10 drops every 1-2 hrs.

(5) Houttuynia. Actions: Moderately broad spectrum antiviral, prevents viral infections if taken prophylactically. Also antifungal, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-cancer, antioxidant. Good against flu, SARS, dengue, enterovirus, herpes, any bacterial diarrhea, staph, strep, bacterial diseases of the eye (fresh juice or tea applied), urinary infections, bartonella of Lyme.

Prep. Pick leaves fresh at flowering and make tincture immediately. 1:2 with 190 proof alcohol. Grind in blender, pour in jar, cap, shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, then run rest through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

Dose. Take 1/4 – 1/2 teaspoon up to 6x daily, depending on how acute the condition is.

Prep. Pick leaves fresh at flowering and make tincture immediately. 1:2 with 190 proof alcohol. Grind in blender, pour in jar, cap, shake 2x/day for 2 weeks. Strain, then run rest through wheat grass juicer. Store in dark bottles in dark place.

Dose. Take 1/4 – 1/2 teaspoon up to 6x daily, depending on how acute the condition is.

(6) Isatis. Actions: Broad spectrum and potent antiviral, and prophylactic. Potentiates viral vaccines, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-parasitic, anti-tumor. Good against flu, rubella, respiratory viruses, measles, mumps, staph, leukemic and liver cancer, salmonella, salmonella, SARS, clostridium difficile, viral pneumonia, sore throat, bacterial conjunctivitis, shingles, chicken pox, encephalitis, gastroenteritis. An immune stimulant.

Prep. I am saving the most tricky herb to prepare for last. Buhner likes to use a mixture of roots and leaves: one part root and two parts leaves. Isatis is a biennial. It goes to flower in the second year. It produces copius seeds, but it is allelopathic to itself, which means you must plant it in new areas each time. It can be invasive given the large number of seeds. It is a most valuable antiviral and worth the trouble.

- Leaves. Harvest the leaves in the first year and beginning of the second year before the plant goes to flower. Harvest older, bigger leaves first, leaving some of them to feed further growth. As the plant grows, it will produce more leaves for you to harvest. When the plant is cut or leaves damaged, later leaves produce much more of the active ingredients. The leaves must be dried before tincturing. Fresh leaves are used to make a blue dye (indigo). Dry at 100 F (dehydrator with a thermostat is best). This improves extraction of the beneficial plant compounds and converts the chemicals to their final form. Store in plastic bags (double bag/zip bags) in a cool, dry place until you have enough to process. Will keep for a few years.

- Roots. Harvest roots in the fall of the first year or the spring of the second year. Clean and slice thinly (as carrots) and dry them in a warm location out of sunlight (or in a dehydrator at 100 F). Store in separate plastic bags in a cool, dry place. Roots keep for a few years.

- Making the tincture. From Buhner, use a herb:liquid ratio of 1:5, with the liquid being 25% alcohol. Remember, Buhner uses roots and leaves in a 1:2 ratio. Let’s suppose you want to make a small batch. Use 1 oz roots and 2 oz leaves. Pulverize separately in a coffee grinder. That gives you 3 oz. The ratio is 1:5, so you will use 3 x 5 or 15 oz liquid, but this liquid is 25% alcohol. Starting with 190 proof alcohol (95%, but use 100% for calculation purposes) you would use 75% water and 25% alcohol. 75% of 15 oz is 0.75 x 15 = ~11 oz water and 4 oz alcohol (the balance of 15 oz).

- You are next going to “cook” the mix of dry herbs in the 11 oz of water. Add the herbs and water to a pot. If you have hard water, add a teaspoon of vinegar to the pot to help extract the alkaloids. Of course, if you are making a larger batch, use more vinegar. Cover the pot and bring the pot to a boil for 30 minutes. Let this be a low boil, as your mixture will get thick and bubble as if it were roofing tar. Stir to prevent sticking. Let it cool to room temperature (or carefully cool in a cold water bath if you are in a hurry).

- Next, pour into a large jar with a lid and add the 4 oz of alcohol. Let it sit for 2 weeks, shaking every now and then. When done, pour off the liquid into a separate container and squeeze the herb slurry through a strainer to get out more of the liquid. Run the strained herb slurry through a wheat grass juicer to express even more. Store the liquid in a dark jar and label. Compost the pressed herbs remains (called "marc").

- Decant into a dropper bottle for use. Given the larger amount you might end up using during a bout of a respiratory infection, I find that a 2 oz dropper bottle is a minimum size.

Tip 1: when decanting from the large jar into a 2 oz dropper bottle, which has a narrow opening, I use a glass pyrex

measuring cup which has a nice narrow spout. I fill to the 2 oz gradation and then pour into the dropper bottle. I label the

bottle with instructions glued to the bottle with rubber cement.

Tip 2: many tinctures have sediments. These are good. Don’t strain out. They tend to settle to the bottom. Before decanting

from the larger jar to the dropper bottle via the measuring cup, shake well. Then decant. Before use, shake dropper bottle

well.

Dose. As a preventative, 30 drops (~ 1/8 teaspoon) 6x daily. For acute conditions 1 teaspoon up to 10x/day. I take 1 teaspoon every 2 hrs during a 12 hr day, which means 7 doses, starting at 9 am and ending with the last dose at 9 pm. I set my countdown watch timer for 2 hr intervals. Remember to shake well before each use. Buhner recommends not taking this herb alone, but using other herbs with it. He likes lomatium or licorice. I use elder, boneset, or houttuynia. Do not take longer than 3 weeks. Over-use may cause weakness, dizziness, and affect kidneys.

Our Experience with Buhner Herbs

Endnote (1) Stephen Buhner's reply to the question "Do herbal remedies kill beneficial microbes?"

In general, no plants do not kill beneficial bacteria. The answer is complex with caveats. Plants are exceptionally good at creating a sophisticated complex of compounds to accomplish what they wish, they have had hundreds of millions of years at it

They are exceptionally sensitive to ecological balancing so, they tend to focus on outcomes, not general shotgun approaches to problems. Their compounds are carefully constructed to kill bacteria that mean them harm. They tend to embed the “active” antibacterial within a complex of other compounds so that the killing action is highly focused.

A related perspective . . . our primary and main defense against bacterial disease is in fact other bacteria, the ones that are commensal with our own evolution. They cover our skin and every mucosal surface that is touched by the outside world. They don’t kill each other but rather bacterial species that are inimical to us. We have helpful staph bacteria on those surfaces that in fact attack pathogenic staph that tries to get a foothold in our systems.

Those commensal bacteria do not attack other commensal bacteria.

Plants who make berberine, which is a highly toxic antimicrobial, also make other substances that moderate that toxicity in their own bodies. The berberine is then focused outward and not inward.

This is just a brief touch on all this but hope it gives a bit of an answer to your questions.

Most plant antibacterials, when taken by people, don’t tend to disturb the gut microflora for this same reason, but can do so if large quantities are taken for extended times to treat acute conditions. Nevertheless, they do not do the same kind of damage that

pharmaceuticals do. March 13, 2018

In general, no plants do not kill beneficial bacteria. The answer is complex with caveats. Plants are exceptionally good at creating a sophisticated complex of compounds to accomplish what they wish, they have had hundreds of millions of years at it

They are exceptionally sensitive to ecological balancing so, they tend to focus on outcomes, not general shotgun approaches to problems. Their compounds are carefully constructed to kill bacteria that mean them harm. They tend to embed the “active” antibacterial within a complex of other compounds so that the killing action is highly focused.

A related perspective . . . our primary and main defense against bacterial disease is in fact other bacteria, the ones that are commensal with our own evolution. They cover our skin and every mucosal surface that is touched by the outside world. They don’t kill each other but rather bacterial species that are inimical to us. We have helpful staph bacteria on those surfaces that in fact attack pathogenic staph that tries to get a foothold in our systems.

Those commensal bacteria do not attack other commensal bacteria.

Plants who make berberine, which is a highly toxic antimicrobial, also make other substances that moderate that toxicity in their own bodies. The berberine is then focused outward and not inward.

This is just a brief touch on all this but hope it gives a bit of an answer to your questions.

Most plant antibacterials, when taken by people, don’t tend to disturb the gut microflora for this same reason, but can do so if large quantities are taken for extended times to treat acute conditions. Nevertheless, they do not do the same kind of damage that

pharmaceuticals do. March 13, 2018